Will #MeToo Ever Reach the Music Industry?

Written by Adison Eyring on February 22, 2019

When accepting the Brit award for Best British Group, a category in which only one out of five acts nominated include any women and in which no female-fronted group has ever won, The 1975 frontman Matty Healy took the opportunity to call out the ingrained misogyny within the music industry. Quoting Guardian writer Laura Snape’s essential essay on abusive male musicianship, Healy said:

Male misogynist acts are examined for nuance and defended as traits of ‘difficult’ artists, while women and those who call them out are treated as hysterics who don’t understand art.

The quote in particular, both in Healy’s speech and Snape’s original essay, seems to be in direct response to the recent New York Times article that reported singer-songwriter Ryan Adams’s track record of using his high status in the indie scene to sexually and emotionally abuse and manipulate young female artists.

Though throughout this article I generalize victims of abuse within the music industry as women and their abusers as men (and, to be clear, this is not an unwarranted generalization to make), there is no doubt in my mind that there are male victims, female abusers, and same-sex abuse. There always are. With male abuse victims often being stigmatized and mocked, it is understandable that more have not come forward.

Because of the #MeToo movement in Hollywood and the recent prevalence of the oft misused and misunderstood “cancel culture,” many seem to believe that the music industry is much better at sniffing out and justly punishing abusers than they truly are. In truth, music executives, artists, fans, and journalists alike have all been knowledgeable and complicit; the abuse and misogyny rampant in the music industry isn’t and has never been a well-kept secret.

The abuse and misogyny rampant in the music industry isn’t and has never been a well-kept secret.

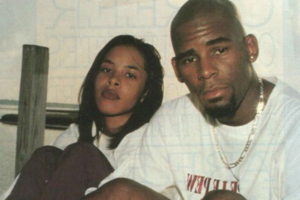

John Lennon beat his wife and “muse” Yoko Ono. Kanye West abused and continually harassed Amber Rose, who is credited with being the main inspiration for his best album. Stephen Tyler had sex with a minor and pressured her into getting an abortion. John Phillips of the legendary folk band The Mamas and The Papas drugged and raped his daughter. R Kelly, among a laundry list of other offenses, married Aaliyah when she was just fifteen years old and he held a position of power over her.

R Kelly and Aaliyah | Photo via The Source

We know all of these heinous things about high profile, widely praised music acts and more. Whether the abuse is an unaddressed but widely known fact or an industry secret most commonly shared in hushed warnings between women, there is enough information out in the open for action to be taken. Why, then, has so little been done?

Perhaps it’s the culture around musicians that has made it so hard for the Me Too movement to permeate the music industry – an industry in which misogyny and abuse flow freely across all genres and levels of corporatism. When Kevin Spacey was exposed as an abuser, House of Cards ultimately only lost an actor. The lead actor, yes, but a replaceable cog in a continually functioning machine nevertheless.

Perhaps it’s the culture around musicians that has made it so hard for the Me Too movement to permeate the music industry – an industry in which misogyny and abuse flow freely across all genres and levels of corporatism.

Though fighting sexual abuse in other entertainment industries certainly hasn’t been smooth sailing, the music industry seems especially reluctant to ostracize known abusers outside of a few niche music markets. The tone when the male artist in question is a musician seems to immediately shift: These things happen. Ignition (remix) still slaps. It’s the price of male genius. It’d be unfair to throw away the art with the artist. C’est la vie. Besides, the pain of a few women here and there simply can’t compare to the cultural importance of Ryan Adam’s milquetoast album of acoustic Taylor Swift covers. I get it.

In music, a form of art in which the artists themselves are 50% of the product, the artist cannot simply be replaced. The art cannot continue without the mouthpiece, and we seem to have deemed the potential loss of art as more severe than women’s physical and mental well being.

When we make statements like, “I obviously hate R Kelly, but his music is still good” (a sentence I have heard shockingly often and from people I respect), we are not only condoning his actions but telling the women abused – artists, creatives, and people in their own right – that their livelihoods are not as important as men’s art. We assure male artists that if they’re good enough at their art (at once something intimately personal and something one can allegedly separate from the artist if need be) their actions don’t matter.

https://twitter.com/carmenmmachado/status/983698931300360192

If we allow these men to continue to work, to make money off of what we consume, even in best case scenarios where the artist has truly gone to great lengths to successfully reform themselves, the lack of any real consequences sends a clear message to artists with less power: At any given moment, this man, or any man, could violate you and ruin your career in the blink of an eye, and he would be absolutely fine.

I understand this is a bleak topic, particularly if you yourself are a victim of abuse or marginalization, and I don’t want to leave the subject without presenting an alternative. What do we do about abuse in the industry? What power do we, as not only audiences but young people with social platforms, have in this context? I’d argue quite a bit. I don’t know how to reform abusers into good people. I don’t know how to systematically change an industry. None of us do. What we can do as consumers is stop directly supporting known abusers by streaming their music or buying tickets to their tours. What we can do as people with social media accounts is stop mourning the “ruined careers” of these men.

What do we do about abuse in the industry? What power do we, as not only audiences but young people with social platforms, have in this context?

Instead, think of women and girls like Ava from the Ryan Adams story: a young female musician who was exploited by her idol for sex, and became so traumatized that she felt she wasn’t cut out for the music industry. Mourn the music we may never get from these women, and provide them support so that one day they’ll feel safe enough to return.

And while we wait for those survivors to heal, listen to the thousands of women who are releasing music every day. Think of artists like Phoebe Bridgers from that same Adams story, who was a victim and still went on to be wildly successful in her own right. If you’re a writer for this publication or another, I implore you to write about them and find the genius in their art. For every violent abuser or misogynist Twitter asks you to cancel, I promise you there is a much more talented female artist behind him who has likely been victim to some of the same atrocities that he exposed others to.

If you’re a man who feels sympathetic or weirdly guilty reading this, listen to more female artists. If you’re a woman or nonbinary person who feels hopeless reading this, listen to more female artists. If you’re enraged by this article and think I am being a hysteric who doesn’t understand art, good – might I recommend my playlist of some of my favorite angry ragers written and/or performed by women? Cheers.

If you’re inspired by the call to listen to more female artists and looking for more resources outside of the above playlist, subscribe to our site to be notified about our recurring feature – Fresh Female Finds.